“Charlie and I enjoy issuing Berkshire stock about as much as we relish prepping for a colonoscopy.”

– Warren Buffett, 2009 Berkshire Hathaway annual report

F our years have passed since Berkshire Hathaway announced that it would acquire Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) in a cash and stock transaction. The acquisition was explicitly meant to be an “all-in wager on the economic future of the United States” according to Berkshire Hathaway Chairman Warren Buffett. In November 2009, the United States was starting to emerge from the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression and purchasing a major railroad was a controversial move based on what appeared to be a relatively full valuation. Enough time has now passed to revisit the rationale behind the acquisition and to judge how the railroad has performed in the midst of a slow economic recovery.

our years have passed since Berkshire Hathaway announced that it would acquire Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) in a cash and stock transaction. The acquisition was explicitly meant to be an “all-in wager on the economic future of the United States” according to Berkshire Hathaway Chairman Warren Buffett. In November 2009, the United States was starting to emerge from the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression and purchasing a major railroad was a controversial move based on what appeared to be a relatively full valuation. Enough time has now passed to revisit the rationale behind the acquisition and to judge how the railroad has performed in the midst of a slow economic recovery.

Terms of Acquisition

The acquisition was finalized in February 2010 when Berkshire paid total consideration of $26.5 billion in cash and stock to purchase all outstanding shares of BNSF that Berkshire did not already own. The total consideration consisted of $15.9 billion in cash and $10.6 billion of newly issued Berkshire common stock. Berkshire raised approximately $8 billion of debt at the corporate level to fund the cash component of the transaction along with an equivalent amount of cash on hand.

Perhaps the most controversial and painful aspect of the acquisition involved the issuance of Berkshire Hathaway common stock at a time when the shares were trading at a relatively low valuation. Berkshire’s book value per class A share was $84,487 at the end of 2009 and the shares were issued at a price of $111,453 implying a price/book ratio of 1.32. Although Berkshire’s price/book ratio subsequently fell to much lower levels in 2011, shares are now trading at a price/book ratio of 1.36. Historically shares have traded at an average valuation of 1.5 times book value.

Using undervalued stock to fund part of the transaction bothered Mr. Buffett but he believed that the terms of the overall deal still made economic sense:

In our BNSF acquisition, the selling shareholders quite properly evaluated our offer at $100 per share. The cost to us, however, was somewhat higher since 40% of the $100 was delivered in our shares, which Charlie and I believed to be worth more than their market value. Fortunately, we had long owned a substantial amount of BNSF stock that we purchased in the market for cash. All told, therefore, only about 30% of our cost overall was paid with Berkshire shares.

In the end, Charlie and I decided that the disadvantage of paying 30% of the price through stock was offset by the opportunity the acquisition gave us to deploy $22 billion of cash in a business we understood and liked for the long term. It has the additional virtue of being run by Matt Rose, whom we trust and admire. We also like the prospect of investing additional billions over the years at reasonable rates of return. But the final decision was a close one. If we had needed to use more stock to make the acquisition, it would in fact have made no sense. We would have then been giving up more than we were getting. Source: 2009 Berkshire Hathaway annual report

Mr. Buffett’s comments are interesting for a number of reasons. Most significantly, he makes the point that using undervalued shares of Berkshire to fund part of the transaction could make sense in the context of the overall deal if the alternative was for the transaction to not happen at all. However, he notes that the decision was a close call implying that any further issuance of stock at an equivalent or lower valuation would have made the overall deal unattractive. He also justifies the transaction by noting that Berkshire would now have the opportunity to invest additional billions of dollars over the years at a reasonable return. In light of these comments, we will take a brief look at BNSF’s operating performance since the acquisition. In addition, we will look at whether Berkshire is starting to direct additional cash to BNSF.

Performance Since Acquisition

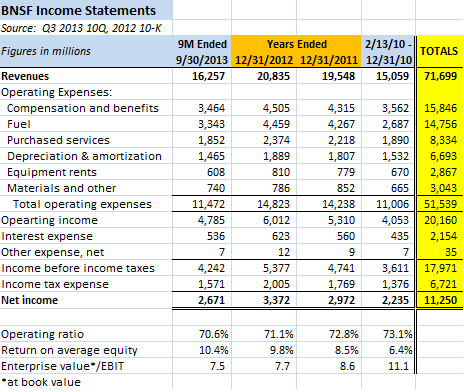

It is not surprising to see that BNSF’s financial results have been on an upward trajectory since the acquisition was finalized in February 2010. Railroads are economically sensitive and freight volumes are highly correlated with overall economic activity. The economy has not been growing particularly quickly over the past few years but the expansion has progressed at a slow pace. The following exhibit shows BNSF’s income statement during Berkshire’s ownership.

Berkshire’s financial statements only include very limited data on the railroad operations but BNSF has continued to file with the SEC separately. Although BNSF’s disclosures under Berkshire’s ownership have not been as comprehensive as when the company was publicly traded, we have enough information to make some general comments.

We can see that revenues have been on an upward trajectory as we would expect with 2013 revenues to date running at an annualized pace of $21.7 billion compared to $20.8 billion in 2012 and $19.5 billion in 2011. However, operating income has been rising at a faster rate than revenues due to improved efficiencies that have driven the operating ratio down to 70.6 percent for 2013 to date compared to 73.1 percent during Berkshire’s period of ownership in 2010. A railroad’s operating ratio is calculated as the percentage of revenues consumed by operating expenses. Another way to look at this is to observe that BNSF’s operating income for the first nine months of 2013 would have been $412 million lower had the operating ratio remained at 2010 levels rather than improving by 2.5 percentage points.

The exhibit also shows BNSF’s return on equity for each period presented. This metric has also been on an upward trajectory with ROE at 10.4 percent for the first nine months of 2013 on an annualized basis. We also compute the ratio of BNSF’s enterprise value (at book value) to earnings before interest and income taxes. We can see that this measure has fallen from 11.1 to 7.5 over the past few years. As we will suggest later, this has implications regarding the current market value of BNSF.

Overall, BNSF has posted strong results since the acquisition with modest revenue growth and a declining operating ratio driving significant improvements when it comes to return on equity. Much of this performance can be attributed to the economy in general but management has also obviously been keeping a close eye on expenses. The operating ratio may be expected to fall during an economic expansion due to economies of scale but probably would not have fallen as much without directed efforts.

Capital Allocation

During the period before and shortly after the acquisition was finalized, there was much talk in the investing community regarding BNSF having similarities to Berkshire’s utility businesses in the sense that both could be expected to earn reasonable returns on invested capital. Berkshire Hathaway has long had the “high class problem” of generating significant cash through its ownership of a wide variety of operating businesses. Since Berkshire has not historically repurchased significant shares and does not pay a dividend, management is constantly looking for places to deploy capital at attractive rates of return. Many observers expected that Berkshire would deploy additional capital toward BSNF in an effort to aggressively expand the railroad.

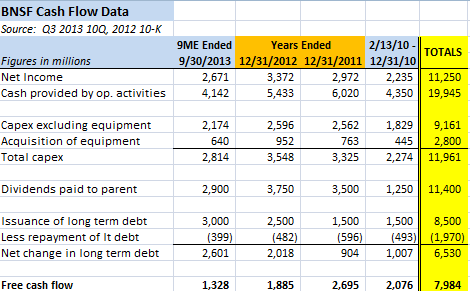

The following exhibit shows selected cash flow information for BNSF since the acquisition was finalized.

It is clear that BNSF is plowing a significant amount of cash into capital expenditures. However, limited disclosure in BNSF’s filings since the merger do not clearly differentiate between the significant maintenance capital expenditures required to keep the railroad’s current capabilities operational and capital expenditures intended for expansion. It is also clear that Berkshire has not been directing additional capital to BNSF so far. In fact, the opposite is true: Berkshire has been receiving significant cash from BNSF in the form of dividend payments. In fact, the dividends paid to Berkshire are close to total BNSF capital expenditures in magnitude. BNSF has been able to both fund its capex program and pay significant dividends to Berkshire by taking on additional debt over the years. Debt as a percentage of total capital has risen from 24 percent shortly after the acquisition to 33 percent as of September 30, 2013.

Shortly after the acquisition was finalized, we made note of BNSF’s first dividend payment to Berkshire but concluded that it was far too early to make any conclusions regarding the overall capital allocation strategy. While a bit under four years is not necessarily “long term”, it does seem like enough time has now passed to come to the conclusion that Berkshire is looking at the railroad more as a source of cash rather than as a destination for cash. One could view the increased leverage at BNSF as a replacement for leverage that Berkshire took on at the corporate level in order to fund approximately $8 billion of the cash component of the purchase. However, at this point, Berkshire has received $11.4 billion from BNSF which more than offsets that initial debt.

What is BNSF Worth Today?

It is impossible to know exactly what BNSF would be worth today as a public stand-alone company but it is very likely that the company would be worth far in excess of Berkshire’s purchase price or BNSF’s current carrying value. We will look at two approaches to estimate what BNSF might be worth today with the understanding that precision in the estimate is not the main goal. Instead, the idea is to confirm that BNSF would very likely trade at a much higher valuation today.

Union Pacific is clearly the most comparable railroad both in terms of overall size and the geographic foot print of the rail network. As such, it is useful to examine Union Pacific’s stock price over the past few years. The chart below displays Union Pacific and Berkshire’s stock price performance since February 12, 2010. Note that by using the date of the completion of the BNSF transaction rather than the announcement of the merger, we are excluding any appreciation in Union Pacific shares due to knowledge of Warren Buffett’s enthusiasm for western railroads.

Union Pacific common stock has rocketed up by nearly 150 percent in addition to dividends paid to shareholders over the past few years. This performance far outpaced Berkshire’s stock price appreciation during the same period. We include Berkshire in the chart for the simple reason that part of the BNSF acquisition was funded with Berkshire shares so it is relevant to look at the relative price performance between Berkshire and the nearest comparable railroad.

Although the chart is interesting, we probably should not rely only on the market to inform our opinion regarding BNSF’s current market value. As an imperfect alternative, it is interesting to look at the enterprise value of BNSF as a multiple of earnings before interest and taxes. We calculate enterprise value as the book value of BNSF equity (which was initially set to Berkshire’s acquisition consideration in February 2010) plus long term debt less cash. As of September 30, 2013, enterprise value was $48.4 billion calculated using this methodology with equity comprising $34.1 billion of the total.

As the income statement exhibit above shows, the EV/EBIT ratio has fallen from 11.1 during 2010 to 7.5 for the first nine months of 2013 when enterprise value is measured using book value of equity. However, if we assign the same 11.1 EV/EBIT multiple that prevailed in 2010 to BNSF’s annualized EBIT for 2013, enterprise value should be $70.8 billion rather than $48.4 billion. If we subtract BNSF’s $17.1 billion of debt, the implied value for the equity would be $53.7 billion which is 57 percent higher than current carrying value of BNSF equity on the balance sheet.

Conclusion

The BNSF acquisition was highly controversial when it was announced four years ago but it has clearly worked out quite well for Berkshire so far. The operating metrics show significant improvements due to a combination of modest revenue growth and much better operating efficiency. It seems highly likely that BNSF would be worth significantly more today than the amount it is carried at on Berkshire’s balance sheet.

The major piece of the puzzle that remains unresolved is whether BNSF represents a source of cash for Berkshire in the coming years or a destination for cash generated by other Berkshire operating units. At the time of the acquisition, we were certainly led to believe that BNSF represents an opportunity similar to Berkshire’s utility business. Cash could be directed to the rail operations and generate a reasonable rate of return over very long periods of time. Thus far, this has not been the case. Berkshire has been drawing cash from BNSF ever since the acquisition was finalized in 2010. As shareholders, we would not want BNSF to embark on ill conceived capital expenditure programs simply to consume free cash flow. Although four years is not necessarily “long term”, it is perhaps enough time to note a trend that should be monitored over the next several years for any signs of a change in direction.

Disclosure: Individuals associated with The Rational Walk own shares of Berkshire Hathaway.