“So the really big money tends to be made by investors who are right on qualitative decisions but, at least in my opinion, the more sure money tends to be made on the obvious quantitative decisions.”

— Warren Buffett, letter to partners, October 9, 1967

As Warren Buffett wrote these words to his partners in late 1967, he was writing from the perspective of a 37 year old man who was about to wrap up the eleventh year of his partnership having achieved gross returns of 1606.9%, which represents annualized returns in excess of 29 percent. For a number of years, Mr. Buffett had been warning his partners that future results would not come close to his past track record. However, in 1968, the partnership posted its highest ever gross return of 58.8 percent which exceeded the return of the Dow Jones Industrial Average by an amazing 45.6 percent. Then in May 1969, with assets under management exceeding $100 million ($~650 million in 2016 dollars), Mr. Buffett announced plans to close the partnership and retire.

The idea of closing up shop with an unparalleled thirteen year track record and assets under management growing at a tremendous clip probably seems crazy to most modern-day investment managers. Although Mr. Buffett did not charge a fixed annual management fee like most other funds, he was entitled to 25 percent of all profits over a six percent hurdle rate. Even if his performance was destined to fall to 10 percent, on average, he would have generated fees of at least $1 million per year in 1970s dollars. However, by the late 1960s, he was securely rich and did not want to be “totally occupied with out-pacing an investment rabbit all my life.” The only way to slow down, in his view, was to stop. Jeremy Miller’s new book, Warren Buffett’s Ground Rules, does an excellent job of putting the Buffett Partnership letters into context. Perhaps more significantly, Mr. Miller draws a number of lessons from the letters that are potentially just as actionable for investors today as they were for Mr. Buffett five decades ago.

The Buffett Partnership letters have been available for a number of years and many investors understandably pored over the details chronologically in an attempt to replay the amazing track record and come up with applicable lessons. However, just as Lawrence Cunningham added significant value putting the Berkshire Hathaway annual letters into context, Mr. Miller’s efforts with the partnership letters have revealed valuable insights that a chronological reading might miss.

For practicing investors today, the most valuable section of the book is Part II where Mr. Miller goes through the three main categories of Buffett Partnership investments: The Generals, Workouts, and Controls. All three represent fields where modern-day investors can look for bargains with an individual’s area of focus depending mostly on temperament, circle of competence, and assets under management.

The Generals

The Generals were companies that made up a concentrated portfolio of undervalued securities that represented the majority of overall partnership gains. With only one exception, Mr. Buffett never discussed any of the Generals with his partners or even disclosed the names of the companies. This strict secrecy might appear eccentric to investors today. After all, we see famous hedge fund managers on television describing their favorite investments all the time. Mr. Buffett’s desire for secrecy, even when he was relatively unknown, stemmed from his lack of interest in seeking out fame as well as his desire to continue accumulating shares of his favorite investments at low prices. There was no incentive for him to reveal his portfolio and invite “coat-tailing”. According to the book, the partnership would typically have 5-10 percent positions in five or six generals with a number of smaller positions adding another 10-15 percent in aggregate.

How did Warren Buffett go about selecting the Generals?

He was constantly appraising the value of as many stocks as he could find, looking for the ones where he felt he had a reasonable ability to understand the business and come up with an estimate for its worth. With a prodigious memory and many years of intense study, he built up an expansive memory bank full of these appraisals and opinions on a huge number of companies. Then, when Mr. Market offered one at a sufficiently attractive discount to its appraised value, he bought it; he often concentrated heavily in a handful of the most attractive ones.

Imagine for a moment Warren Buffett sitting in his office in the late 1950s with The Wall Street Journal, a Moody’s Manual, a pile of printed annual reports, a notepad, and a pencil. These were the tools of his trade at the time when he was coming up with these lists of investment candidates. There was no SEC website, no access to spreadsheets like Microsoft Excel, no way to research companies except to send out for information, and he didn’t even have an HP-12C. The idea of coming up with a list of hundreds of investment candidates and then keeping up with them and gauging their relative attractiveness is hardly an easy task with modern resources but it is certainly possible for diligent investors. In the 1950s and 1960s, raw memory, intellect, and work ethic were probably greater competitive advantages than they are today, but the right temperament, which is timeless, is even more critical.

Workouts

Merger arbitrage was a major source of investment ideas and profit for the Buffett Partnership throughout its history. As Mr. Buffett was wrapping up the partnership in 1969, he lamented that his performance in workouts that year had been “atrocious”. Indeed, merger arbitrage was a hazardous activity in the 1960s and remains so today, except now there is far more information and efficiency which could make this field more challenging.

For the partnership, the overall experience in workouts was positive due to Mr. Buffett’s skill and insight into which deals to bet on. When an acquisition is announced, the spread between the price the target company’s stock trades at and the offer price represents potential profit to an investor purchasing the stock. The degree to which the investor can profit depends on the size of the spread, the amount of leverage used, the amount of time between buying the target’s stock and the transaction closing, and whether the deal actually does close or falls apart. The situation becomes much more complex when an offer involves the acquiring company’s stock rather than cash.

Despite the risks, workouts represented an attractive field for the partnership both because of the profits they generated and due to the fact that these returns were uncorrelated to the overall stock market. In most years, workouts made up 30-40 percent of partnership assets. When the overall level of the stock market was rising, Mr. Buffett would tilt the partnership away from Generals and toward Workouts. When the stock market was falling, he would allocate more capital toward Generals and less toward Workouts.

In contrast to the secrecy surrounding Generals, Mr. Buffett was more willing to discuss Workouts once they were fully … worked out. Mr. Miller presents one such case study regarding Texas National Petroleum from the 1963 letter. In considerable detail, Mr. Buffett describes how he came up with the idea, researched the matter in great detail, and profited from the spread that emerged. One interesting item to note is that the company’s management was often available to comment on how the process was going. While perfectly legal, ethical, and appropriate based on the rules in existence at the time, it isn’t clear whether managers today would be willing to discuss the progress of a transaction with an outside shareholder.

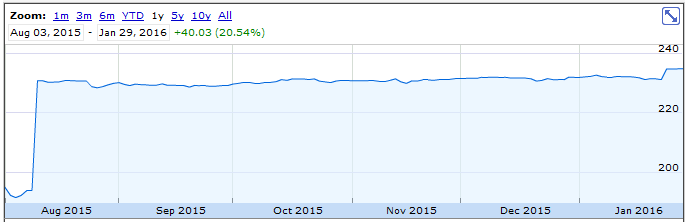

Modern-day investors can pursue workouts today but have to use a great deal of caution. One potential field for consideration might involve looking at deals that involve Berkshire Hathaway. For example, when Berkshire announced the Precision Castparts acquisition in August 2015, Precision Castparts shares did not trade up to the $235 offer price. Shares jumped from around $193 on the day before the announcement to slightly over $230 on the day of the announcement. One could purchase shares at $230 in mid-November and at a little over $231 just days before the acquisition closed in January 2016:

Obviously buying shares during this period was not entirely risk free. If the transaction fell through for any reason, shares would probably have fallen back to August levels or perhaps even further given the overall market environment in early 2016. However, Berkshire is known for never backing out on acquisitions once announced. The risk seemed quite low. An investor who added leverage and waited until the transaction was about to close could have earned substantial returns.

Is this field risk free or for the faint of heart? Not at all, but this was an important category for the Buffett Partnership and worth examining for those who believe that they have a suitable temperament.

Controls

Berkshire Hathaway’s policy is to never pursue hostile acquisitions and the company does not typically seek to influence the managers of investees. Warren Buffett is not known as an “activist” investor today but that is precisely what he was at times during the 1960s. The most famous example is Berkshire Hathaway itself where Mr. Buffett built up a stake in the company over several years before assuming control and forcing out management. Berkshire started out as a General and morphed into a Control.

Although Berkshire Hathaway might be the most famous example of a Control, Mr. Miller’s coverage of the Sanborn Map Company is a classic that modern-day investors might find it easier to relate to. Sanborn Map made up 35 percent of the partnership in 1959 and concluded successfully in 1960.

Sanborn was a successful publisher of very detailed maps used by insurance companies to assess various risks. The company was a cash cow and management built up a large securities portfolio over a number of years. By the late 1950s, the map business was in decline. The market quotation of Sanborn implied that the map business had negative value, as Mr. Buffett described:

In the tremendously more vigorous climate of 1958 [in comparison to the late 1930s] the same map business was evaluated at a minus $20 [per share] with the buyer of the stock unwilling to pay more than 70 cents on the dollar for the investment portfolio with the map business thrown in for nothing.

The size of the investment portfolio had also made managers and directors complacent and there was a lack of urgency in rejuvenating the map business, which Mr. Buffett believed still had positive value. Mr. Buffett joined the board but found that most of the other directors had nominal holdings of the stock and did not share his urgency. In late 1958, an opportunity arose when several unhappy large shareholders decided to sell. However, even in combination with unhappy continuing shareholders, Mr. Buffett lacked an outright majority. Seeking to avoid a proxy fight, a solution was devised to take out all shareholders who wanted to exit:

About 72% of the Sanborn stock, involving 50% of the 1,600 stockholders, was exchanged for portfolio securities at fair value. The map business was left with over $1.25 million in government and municipal bonds as a reserve fund, and a potential corporate capital gains tax of over $1 million was eliminated. The remaining stockholders were left with a slightly improved asset value, substantially higher earnings per share, and an increased dividend rate.

In this example, we see an investor who was not yet thirty years old take effective control of a company founded in the late 1800s and devise a solution that not only resulted in significant gains for the partnership but also a positive outcome for continuing shareholders of Sanborn. So, while Warren Buffett was an “activist” in his early years, the basic elements of fair dealing that he is known for today were already present.

George Risk Industries – A Modern Day Potential Control?

Are there still situations like Sanborn Map? The situation at George Risk Industries in early 2010 was not identical to Sanborn Map but it “rhymed” in certain ways. George Risk, founded in 1965, had an operating business but was massively overcapitalized with a large securities portfolio. The son of the company’s founder served as CEO and had a controlling interest. With a market capitalization of just over $20 million at the time, the company also traded below net current assets.

Fast forward to 2016 and not much has changed. The founder’s son passed away and his daughter took over as CEO. The family still has a majority interest in the company. The valuation of the company has nearly doubled to around $37 million and shareholders have received meaningful dividends throughout the period. The company is still massively overcapitalized. Returns from owning George Risk have not equaled the return from S&P 500 or Berkshire Hathaway.

Would Warren Buffett, if he had been operating with very little capital in 2010, have attempted to purchase shares of this thinly traded stock? Would he have taken an active role trying to persuade the Risk family to distribute securities to shareholders? We cannot know the answer to these questions but would note that this field of endeavor is still very much open to small investors who have the appropriate temperament, and perhaps more importantly, a great deal of patience and ability to underperform for a long period of time while waiting for the investment thesis to play out.

Anyone who is interested in George Risk has the luxury of access to the SEC database covering almost 20 years of company history, something an investor operating in the 1950s could only dream about.

Closing the Partnership

As one reads the final chapters of the book, we know how the arc of Mr. Buffett’s life will proceed and view the story from that perspective. However, in the late 1960s, it really did appear that Mr. Buffett wanted to slow down. It was clear that he did not want to fully “retire” and intended to take at least an advisory role at Diversified Retailing and Berkshire Hathaway.

Some of you are going to ask, “What do you plan to do?” I don’t have an answer to that question. I do know that when I am 60, I should be attempting to achieve different personal goals than those which had priority at age 20. Therefore, unless I now divorce myself from the activity that has consumed virtually all of my time and energies during the first eighteen years of my adult life, I am unlikely to develop activities that will be appropriate to new circumstances in subsequent years.

It is hard to not observe that Mr. Buffett closed the partnership shortly before reaching 40 years of age. Was this part of a mid-life crisis? Those of us on the far side of the big 4 – 0 might relate to the need to make some sort of reassessment upon the realization that we will soon be closer to receiving Social Security than to our college years. It is obviously true that the environment of the late 1960s, described in detail in the book, was the main factor and Mr. Buffett really did feel like he was out of good ideas that could be implemented within the constructs of a $100 million portfolio. However, it is interesting to get somewhat of a personal window into what went into the decision at this point in his life.

Regardless of intentions, we know that any “slow down” did not last for long. As Chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, Mr. Buffett took the underlying ground rules of his partnership into a corporate form. As the Berkshire Owner’s Manual makes clear, the corporate form has not erased the partnership culture.

Most value investors are familiar with the history of Berkshire Hathaway and with the broad outlines of the Buffett Partnership as documented in excellent biographies such as The Snowball and The Making of an American Capitalist.

Thanks to Mr. Miller’s efforts, we now have the ability, in a concise and efficient format, to explore Warren Buffett’s early years as a professional investor. Whether reading the book for actionable approaches to investing or just out of biographical curiosity, it is definitely time well spent.

Disclosure: Individuals associated with The Rational Walk LLC own shares of Berkshire Hathaway.