Last week, we took a brief look at Berkshire Hathaway’s loss estimation accuracy over the past ten years. As we noted in the article, the process of estimating the ultimate losses resulting from an insurance company’s business is one of the most important tasks facing management. In the case of Berkshire Hathaway, many types of policies expose the company to liabilities that will develop over a very long period of time. Therefore, the ultimate payout to policyholders can vary significantly from management’s original estimate and may not be known for decades.

Auto Insurance and Short Tails

One of Berkshire Hathaway’s insurance subsidiaries is GEICO, a company engaged primarily in providing private automobile insurance in the United States. Auto insurance losses generally have a “short tail” which means that losses tend to be reported quickly and paid out to policyholders. Berkshire Hathaway only reports loss estimate development for all of its insurance subsidiaries in aggregate. Since many Berkshire reinsurance operations write policies with “long tails”, estimation error is more likely to be seen in a consolidated summary of loss development than if we were to look only at a company such as GEICO in isolation.

Progressive’s Loss Estimates: 1999 to 2009

It may be interesting to take a brief look at a “pure play” auto insurer to see how the loss triangle table would look for an insurance company focusing on “short tail” coverage. In theory, the accuracy of initial estimates should be fairly high and could be expected to develop fully within a couple of years in contrast to the experience of a typical reinsurer.

It may be interesting to take a brief look at a “pure play” auto insurer to see how the loss triangle table would look for an insurance company focusing on “short tail” coverage. In theory, the accuracy of initial estimates should be fairly high and could be expected to develop fully within a couple of years in contrast to the experience of a typical reinsurer.

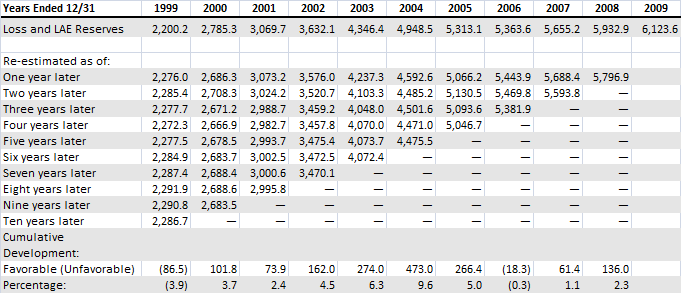

Progressive’s 2009 annual report was filed last week and contains data on loss estimation accuracy for 1999 to 2009. The table shown below provides a summary (figures in millions, click on the image for a larger view):

One interesting aspect of the earlier years is that even when we see that the variance between the original loss estimate and the ultimate figure is large, the amount of the error is mostly known within a few years. For example, in 2004 the original loss estimate of $4,949 million turned out to be higher than necessary. However, the discrepancy was recognized very quickly. By the second year after the original estimate was made, the revised estimate was very close to the current estimate.

While we cannot see GEICO’s results presented in such a granular format within Berkshire Hathaway’s annual report, it is very likely than loss development follows a similar pattern. Management may still make relatively large errors when the initial loss estimates are calculated, but any errors are likely to be corrected within a short period of time. In contrast, management estimates for reinsurance covering claims associated with asbestos health damage may only develop over many decades. In such cases, any estimation problems may remain undetected for very long periods of time.

The lesson to be drawn may be obvious for insurance industry veterans, but is nonetheless worth pointing out: Loss estimates for very long tail insurance is inherently less accurate than for short tail insurance. Furthermore, it may be years or even decades before you know whether a mistake has been made. It is useful to keep this in mind when analyzing insurance companies.

Disclosure: The author has no position in Progressive. The author owns shares of Berkshire Hathaway and is the author of The Rational Walk’s Berkshire Hathaway 2010 Briefing Book which provides a detailed analysis of the company along with estimates of intrinsic value.