“The compensation committee relies on its own good judgment in carrying out its duties and does not waste shareholder money on compensation consultants.”

–Daily Journal Corporation 2013 Proxy Statement

David Larcker and Brian Tayan of the Stanford Graduate School of Business recently published a paper entitled Corporate Governance According to Charles T. Munger which concisely outlines the governance philosophy that Mr. Munger has presented on a number of occasions. While the article will not reveal much new information for longtime students of Berkshire Hathaway, it does explore the key points and asks whether Mr. Munger’s prescription might apply to an average corporation.

Seamless Web of Deserved Trust

Mr. Munger’s approach would be considered radical by most conventional companies for a number of reasons. Perhaps the most radical concept is the idea of a “seamless web of deserved trust”, as quoted in the Stanford paper:

A lot of people think if you just had more process and more compliance—checks and doublechecks

and so forth—you could create a better result in the world. Well, Berkshire has had practically no process. We had hardly any internal auditing until they forced it on us. We just try to operate in a seamless web of deserved trust and be careful whom we trust.

The trust based system, in contrast to one driven by enforced compliance, can clearly be superior because of the greater efficiency competent and trustworthy individuals realize by operating in the best interests of the company without being constantly burdened by bureaucracy. Berkshire Hathaway is the perfect example of a company that historically violated many “good governance” principles such as separating the Chairman and CEO roles yet has delivered exceptional results due to both the ethics and skill of Warren Buffett.

The idea of selecting a CEO and then delegating to him or her nearly to the point of abdication obviously carries a great deal of risk. The most obvious risk is that the board of directors might make a serious mistake in judgment in the CEO selection process. The board might wrongly attribute an executive’s track record to skill when it could have been driven by luck or other external factors or, even worse, the confidence the board places in the executive’s integrity might be terribly misplaced. The seamless web of deserved trust can be broken even in the best corporate cultures. This was most dramatically demonstrated three years ago when David Sokol’s misconduct at Berkshire Hathaway resulted in the removal of a top executive widely thought of as a likely successor to Warren Buffett.

Skin in the Game

A special case of the “seamless web of deserved trust” occurs when the manager of a business owns all of the economic interest as well. In this special case, there are no agency problems and no need for trust since the manager and owner are one and the same. In the world of public companies, even those admirably run, there are always agency issues to be aware of.

A system in which the individuals making decisions do not bear the consequences of those decisions seems incompatible with a seamless web of deserved trust. One of Mr. Munger’s favorite examples, as cited in the Stanford paper, involves the method the Romans used to ensure that engineers had skin in the game. Upon completion of a bridge, the engineer would stand under the arch when the scaffolding was removed.

Actual ownership of equity in the business purchased by the CEO with his or her own money can serve to align interests with shareholders in a way that option grants or restricted stock given to the executive can never match. Mr. Munger advocates restraint in executive compensation and finds it particularly admirable when executives agree to accept below market compensation because they are already rich and have enough of an ownership interest in the business to create automatic shareholder alignment. Obvious examples include Mr. Buffett and Mr. Munger who have received virtually no compensation for their work at Berkshire Hathaway:

Source: Berkshire Hathaway 2013 Proxy Statement

Source: Berkshire Hathaway 2013 Proxy Statement

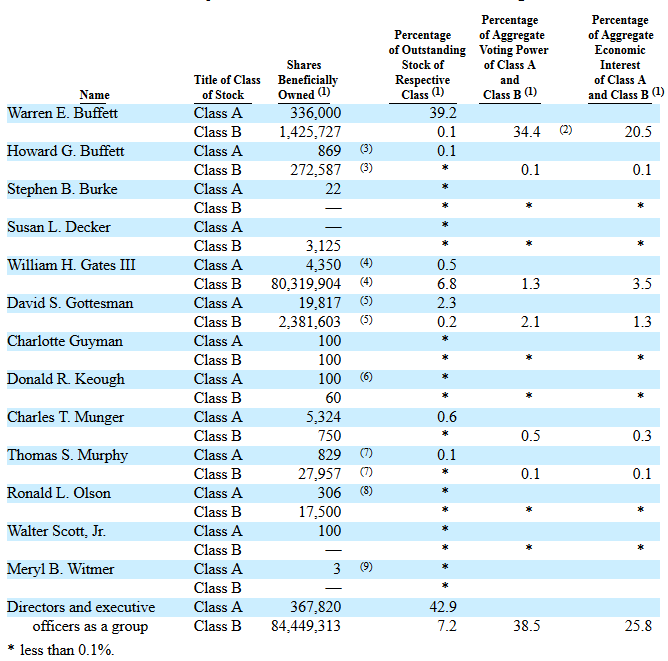

This restraint in executive compensation is only possible because of Mr. Buffett and Mr. Munger’s large holdings in Berkshire Hathaway stock which, along with the rest of the directors, creates a shareholder orientation absent at most large corporations:

Source: Berkshire Hathaway 2013 Proxy Statement

Source: Berkshire Hathaway 2013 Proxy Statement

Is it possible to implement a trust based model for corporate governance without the management having a very large economic interest in the company, both relative to the size of the company and to their own net worth? It is doubtful that such a model could be implemented widely without management having much skin in the game, although there could always be exceptions to a general rule.

Applicability to Investing Decisions

The Stanford paper and our brief commentary does not encompass all or even most of Mr. Munger’s thoughts on corporate governance which might appear simple compared to the conventional approach. However, these ideas are by no means simplistic. Readers who are interested in more of Mr. Munger’s thoughts on corporate governance and many other subjects would be well served to carefully read Poor Charlie’s Almanack.

At the risk of oversimplifying the issue, it does appear almost self evidently attractive to hire intelligent, capable, and ethical managers who personally paid for large economic interests in the businesses that they run. Such managers would require modest executive compensation and could be counted on to advance the interests of all shareholders and to see their net worth rise or fall along with all other shareholders.

The authors of the Stanford paper appear to be interested in whether Mr. Munger’s approach could be widely applied to corporations and the answer is anything but clear. We know that the approach has worked well at Berkshire Hathaway, Costco, The Daily Journal, and a number of other unusual cases but could one hope to achieve the same culture at an existing large company with a conventional structure today?

This question is no doubt interesting to corporate governance experts and academics as well as to entrepreneurs who are setting up a corporate structure and want to emulate Mr. Munger’s approach. However, the lesson for passive minority shareholders without direct influence over corporate governance is a bit different.

In addition to paying attention to executive compensation and corporate governance in general, we should actively look for companies that partially or fully emulate Mr. Munger’s preferred model and give preference to such companies as investment candidates. For those who utilize investment checklists, it is important to include one or more items designed to gauge whether corporate governance seems rational and whether the CEO truly has skin in the game.

Rather than seeking to create companies that have these features, which is bound to be very hard to do, investors have the liberty to not worry so much about how to implement the culture and more about how to identify companies that already have positive shareholder friendly cultures in place. It seems much easier to identify exceptional cases than to create them.