“Without a doubt, Berkshire’s largest unrecorded wealth lies in its insurance business. We’ve spent 48 years building this multi-faceted operation, and it can’t be replicated.” — Warren Buffett, 2015 letter to shareholders

The release of Berkshire Hathaway’s annual report is always accompanied by a great deal of coverage in the media. Although shareholders may prefer to focus on Berkshire’s business results, media coverage tends to look more closely at Warren Buffett’s commentary on a range of economic and political subjects. As a result, it is not unusual for very important insights regarding Berkshire itself to be lost in the noise, whether in print or on television. This was particularly true over the past few days when the media almost completely ignored subtle but important changes in Mr. Buffett’s views regarding Berkshire’s insurance operations.

Importance of Sustainable Underwriting Profits

The barriers to entry in the insurance business are not particularly high and following periods of relative calm, new capital often enters the industry and puts pressure on premium pricing. An insurer’s reputation and capitalization are important factors, but pricing power is not readily apparent. Well run insurers like Berkshire allow premium volume to decline in periods when pricing is inadequate. Insurers lacking this discipline will eventually find themselves with a flood of red ink representing underwriting losses. In severe cases, underwriting losses can exceed the investment income generated from policyholder float rendering the business as a whole unprofitable.

If one relies on the statements made by insurance executives, nearly every insurer has a very disciplined underwriting approach and will reject poorly priced risks. However, the only relevant factor is whether such words are followed by an actual track record of underwriting success. Breaking even from an underwriting perspective allows insurers to profit from investment returns on policyholder float. Insurers that can regularly post underwriting profits turbo charge overall profitability because the float they hold has a negative cost. For further background on the power of negative cost float and consistent underwriting profitability, readers may wish to refer to In Search of the Buffett Premium.

13 Years of Underwriting Profits

Berkshire has posted underwriting profits for thirteen consecutive years totaling $26 billion. This track record, which spans a period that includes several large mega-catastrophes, is particularly impressive given the fact that Berkshire had posted four years of consecutive underwriting losses from 1999 to 2002 primarily driven by very poor results at General Re. Mr. Buffett’s letters from those years go into detail regarding the troubles that became apparent at General Re following Berkshire’s acquisition of the company in 1998.

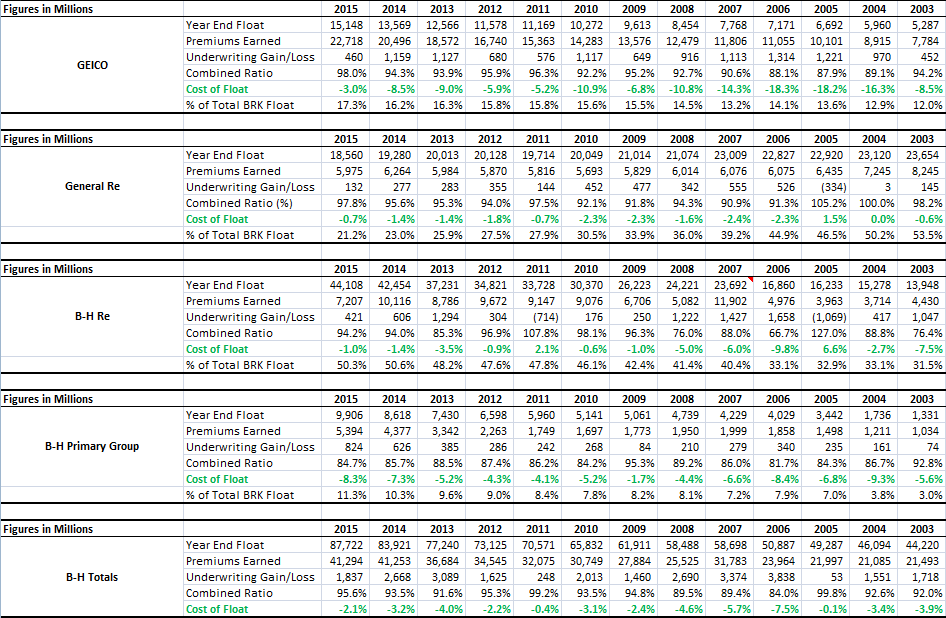

Over the past thirteen years, the track record is remarkable. GEICO and the collection of companies known as the Berkshire Hathaway Primary Group posted underwriting profits every year. General Re posted a single year of underwriting loss in 2005 while Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance posted underwriting losses in two years. The reinsurance business is typically more exposed to mega-catastrophes so the consistent performance of General Re and Berkshire Hathaway Re is quite notable.

The exhibit below shows the relevant data for each of Berkshire’s insurance groups along with consolidated totals. Click on the image for a larger view.

Impact on Berkshire’s Valuation

There are a number of methods that can be helpful for estimating Berkshire Hathaway’s intrinsic value, many of which have been discussed on this website in the past. In Search of the Buffett Premium, published five years ago, provides a summary of valuation approaches that readers might find useful.

Five years ago, Mr. Buffett introduced the concept of three pillars of intrinsic value at Berkshire. Two of the three pillars can be estimated in a quantitative manner and have often been referred to on this website and elsewhere as the “two column” method. Essentially, Berkshire is being viewed as having one area of value in the form of investments funded by shareholders’ equity and insurance float and another source of value represented by non-insurance operating companies. Importantly, the valuation of operating companies has always excluded any sources of earnings from insurance.

In his 2015 letter to shareholders, Mr. Buffett for the first time includes insurance underwriting income in business earnings. This will have the effect of producing a higher capitalized valuation estimate for the operating companies and the change is not insignificant. Mr. Buffett justifies this change in approach as follows:

“…We are for the first time including insurance underwriting income in business earnings. We did not do that when we initially introduced Berkshire’s two quantitative pillars of valuation because our insurance results were then heavily influenced by catastrophe coverages. If the wind didn’t blow and the earth didn’t shake, we made large profits. But a mega-catastrophe would produce red ink. In order to be conservative then in stating our business earnings, we consistently assumed that underwriting would break even over time and ignored any of its gains or losses in our annual calculation of the second factor of value.

Today, our insurance results are likely to be more stable than was the case a decade or two ago because we have deemphasized catastrophe coverages and greatly expanded our bread-and-butter lines of business. Last year, our underwriting income contributed $1,118 per share to the $12,304 per share of earnings referenced in the second paragraph of this section. Over the past decade, annual underwriting income has averaged $1,434 per share, and we anticipate being profitable in most years. You should recognize, however, that underwriting in any given year could well be unprofitable, perhaps substantially so.”

As the exhibit earlier in this article demonstrates, underwriting profit is most variable at Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance due to the nature of the coverage provided. However, the volatility has mostly been within a zone of profitability rather than swinging from profits to loss. With Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance accounting for over half of Berkshire’s total float, one would have to assume that this segment, on a normalized basis, will produce underwriting profitability over a full cycle. It is not particularly hazardous to assume consistent underwriting profitability from GEICO and Berkshire Hathaway Primary on a year-to-year basis and certainly over a full cycle. General Re has volatility in its results but only one year of underwriting losses over the past thirteen years and its importance to Berkshire has shrunk dramatically as a percentage of float.

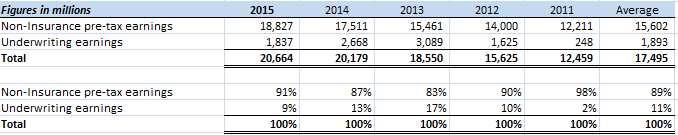

It is up to shareholders whether to take Mr. Buffett’s advice regarding adding underwriting profits to the profitability of Berkshire’s non-insurance subsidiaries and then coming up with a capitalized value for these earnings. Obviously, Mr. Buffett’s advice should carry significant weight given his understanding of the company as well as his inherent conservatism when it comes to providing guidance to shareholders regarding Berkshire’s value. If we take his advice, the impact is likely to be material. The following exhibit shows Berkshire’s non-insurance pre-tax earnings along with underwriting pre-tax earnings for the past five years.

If we add underwriting earnings, the impact would be to increase earnings by around 10 percent on a normalized basis. It would be logical to presume that the valuation of Berkshire’s business units would also rise by about 10 percent, although it might be reasonable to somewhat lower the overall pre-tax earnings multiple to acknowledge the fact that the portion contributed by underwriting is not as robust or predictable as the earnings from Berkshire’s non-insurance operations.

At the end of 2015, Berkshire’s per-share cash and investments were $159,794 per share. This represents the first column in the two column approach.

Pre-tax earnings including Berkshire’s underwriting income but excluding dividends and interest from investments to avoid double counting were $12,304 per share. Of this amount, $1,118 per share is attributable to underwriting income. The capitalized value of this earnings stream represents the second column in the two column approach. Investors typically use a pre-tax earnings multiple to capitalize the earnings. The multiple to use is up to the judgment of the investor. For example, if one uses a 9x pre-tax multiple, this would translate roughly to a 14x after-tax multiple and the capitalized value would be $110,736 per share. Of this value, roughly $10,000 per share would be attributed to Mr. Buffett’s suggestion to start including underwriting profits in the valuation.

Using the assumptions above, the total two column valuation would be $270,530, which we can round to $270,000 per A share and $180 per B share. This represents a rather high 1.74x book value. Using the prior approach excluding underwriting profits, the two column total would be $260,000 per A share and $173 per B share, which would equate to 1.67x book value. These calculations are simply examples and the reader should use his or her judgment regarding the pre-tax earnings multiple to use and whether to include underwriting earnings or not.

Summary

Warren Buffett’s opinion regarding Berkshire Hathaway’s intrinsic value is something intelligent investors should carefully monitor for obvious reasons. No one knows the company better having built it up from a struggling textile mill into today’s enormous conglomerate. However, as intelligent investors, Mr. Buffett would expect us to look at the data and form our own conclusions regarding his recommendation.

From our review, briefly summarized in this article, it appears that there is significant justification for considering normalized underwriting profits to be an enduring source of value for Berkshire. Thirteen years may not be an eternity but it should qualify as a “long term” track record for nearly everyone. This does not mean that Berkshire will never post a year of underwriting losses. It is highly likely that there will be more than one such year over the next thirteen but if normalized results are profitable, such results should be considered as part of Berkshire’s overall valuation.

Readers will have to come up with intrinsic value estimates for themselves but it is hard to justify the recent price of Berkshire Hathaway as being a fair representation of intrinsic value. Indeed, at anywhere close to Berkshire’s repurchase threshold of 1.2x book value, repurchases would immediately add significant value for continuing shareholders.

Disclosure: Individuals associated with The Rational Walk LLC own shares of Berkshire Hathaway