Financial markets have finally come to the realization that Coronavirus is a story that is not going away anytime soon. As long as the virus was confined mostly to China and other cases could be readily explained, markets in the United States appeared complacent. However, reports of an increasing number of cases in Europe over the past week, including some that appeared to be spreading within local communities, caused Wall Street to react sharply in recent days.

For the week ending on February 28, 2020, the S&P 500 was down 11.5 percent. This leaves the index 12.8 percent below its recent record high close on February 19, 2020 well within the “correction” range that is typically defined as a decline of ten percent of more. Of course, the history of the S&P 500 shows that there have been many other precipitous declines including its largest ever one-day drop of 20.5 percent on October 19, 1987, an event also known as “Black Monday”.

Black Monday might be beyond the personal recollection of many investors but the fourth quarter of 2018 should still be fresh in everyone’s memory. From September 20 to December 24, 2018, the S&P 500 declined by 19.8 percent, just under the twenty percent threshold that would have marked the start of a bear market. At Friday’s close of 2,954.22, the S&P 500 is less than one percent above where it stood on September 20, 2018.

While stock markets appeared to be in a near free fall at times, the bond market rallied strongly as worried investors sought the perceived safety of United States government securities. The ten year treasury note started the week at 1.46 percent and fell to 1.13 percent by Friday, February 28 which is an all-time record low yield.1 Since bond prices move in the opposite direction of yields, this means that investors in the ten year treasury saw the value of their bonds rise last week while stock investors suffered losses. Whether “safety” can be attained by purchasing securities at slightly more than a one percent yield issued by a government that has pledged to inflate the currency by two percent per year is a significant long term concern but beyond the reckoning of market participants in the midst of a panic.

This article provides some thoughts regarding how one might keep the situation in the proper perspective, how to think about changes in the valuation of business in response to a pandemic, and finally how the events of the past week might influence Berkshire Hathaway’s repurchase policy.

Keeping Things in Perspective

The Coronavirus situation is a serious public health emergency and people are correct to be concerned that it could turn into a much wider pandemic if steps are not taken to reduce the spread of the virus.2 Personally, I am much more worried about the spread of the virus within my local community in general as well as the risk to friends and family members who might be especially vulnerable.

The effects of the virus on business activity and security prices may well be significant, but in the long run, even the worst pandemics will run their course and conditions will improve. Personal and community preparedness is far more important at this stage than worrying about the prices of financial assets. Money is important but can be replaced whereas lives lost are lost forever. Trite, perhaps, but still very true.

In terms of business activity, a few thoughts on the subject might be helpful when thinking about the potential impact of the virus. It is useless to think in terms of the impact to stocks without considering the impact to the underlying businesses represented by stock prices. The following points might not be particularly insightful but still seem relevant enough to outline briefly:

- Not all businesses are equally exposed. It is obvious that a cruise ship operator, an airline, or an operator of a high end hotel or restaurant in Venice will suffer greater harm from Coronavirus compared to an operator of gasoline stations or grocery stores providing essential products and services needed for daily life. For the most part, financial markets understand this type of “first level thinking” fairly well so we see stocks of airlines, for example, reacting very negatively to the prospect of travel disruptions.

- Some business will be lost forever while other business will be deferred. Tourism seems like a prime example of lost business. Even though some travel will be deferred rather than cancelled, a lost season of spring tourism will never be fully recovered. However, if one considers a case where a manufacturer has suffered supply chain disruptions due to the impact of Coronavirus in China, much of this business might simply be deferred rather than lost forever. However, consumer confidence could come into play and prevent pent-up demand from materializing.

- Leverage can kill. If a business is especially vulnerable to short term impacts of the virus and is also highly leveraged, Coronavirus could literally kill the business. At times like this, financial conservatism is paramount. During good times, leverage accentuates financial results but there is no free lunch available. The same leverage dampens results when times get tough and can be deadly. If you operate a fleet of cruise ships that are temporarily sitting idle at port, you still have to maintain the fleet and pay interest on your debt while your revenue slows to a trickle. How long can you survive?

- Some businesses will benefit. The obvious examples here include companies that are selling equipment or services needed to combat the virus itself. There is currently a major shortage of N95 masks that are said to be partially effective in terms of slowing the spread of the virus. 3M will be able to sell as many of these masks as they can produce for the foreseeable future. Another obvious example includes companies manufacturing drugs or supplies needed in hospitals and other clinical settings. Finally, any company that comes up with a treatment or vaccine will clearly benefit, albeit with political limitations so as not to be seen as pricing treatment at levels perceived to be unfair.

There are certainly other considerations and we should all strive to go beyond first level thinking. One rarely gets paid in financial markets for thinking about the same things that everyone else is thinking about. Since the macroeconomic impacts are being discussed by nearly everyone, chances are that deployment of second level thinking is most likely to be fruitful at the micro level, that is at the level of individual companies.

Intrinsic Value Impact of Disruption in 2020

Unless you are looking at a business that clearly stands to benefit from the Coronavirus, which would be quite rare, it is nearly certain that the businesses you own will suffer some level of harm from this situation, either due to direct impact on business or through macroeconomic effects that could accompany a recession. No one knows the scope of the harm at this point because we do not have any understanding of how widespread the contagion will be. Nevertheless, we should bear several things in mind when we try to evaluate how a business slowdown will affect a particular business.

First of all, as noted above, think about leverage. Can the business survive short term vicissitudes and come out on the other side at all? Intelligent investors will never own companies that do not offer any margin of safety so, hopefully, the question of excessive leverage is one that filtered out such companies from consideration well before this crisis.

Assuming that Coronavirus does not kill the business, the rational way to frame your thinking about intrinsic value is to think about how free cash flow is likely to be impacted over time. And this assessment is going to depend on your judgment regarding how business conditions will develop over time for the company.

The intrinsic value of a business is the discounted value of the free cash flow (FCF) it will generate over the rest of its life. Necessarily subjective and impossible to predict with accuracy, this theoretical construct is still a useful way to think about the impact of any short term shock. Let us take an admittedly simplistic example to illustrate this point. In this example, assume that the business is not leveraged to the point where near term survival is in question.

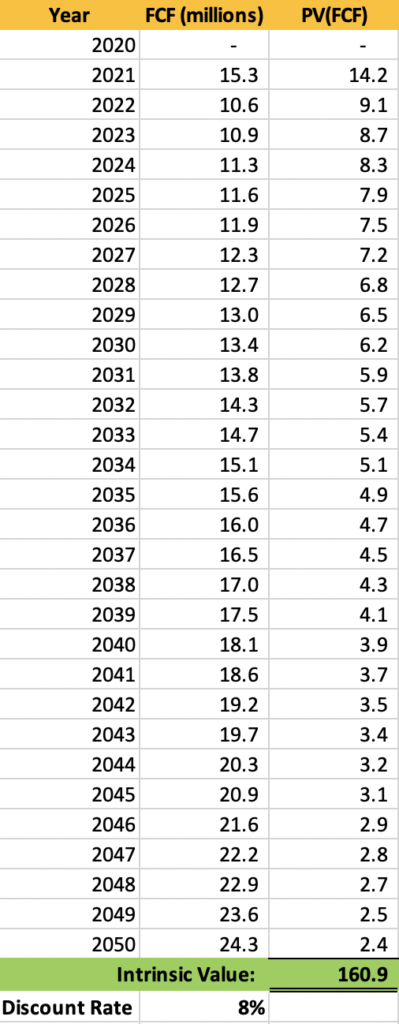

Assume that you have a business that is expected to generate $10 million of FCF in 2020 and is likely to grow FCF at a 3 percent annual rate over the next thirty years. If you use a rate of 8 percent to discount the thirty years of future cash flow into present value terms and add the $10 million of un-discounted current year cash flow, you would arrive at an intrinsic value estimate of a little over $166 million, ignoring any cash flow that might be generated after this thirty year period. Of this $166 million estimate, over half is attributed to cash flow expected from years ten through thirty.

The exhibit below shows each year of expected cash flow discounted to present value terms:

You made these estimates a month ago before the Coronavirus news and now you need to adjust your assumptions based on your assessment of how a pandemic might impact near term and long term free cash flow. The difficulty is in making the assumptions, but it is easy to test your assumptions and see the impact on intrinsic value.

For example, let’s say that you believe that the business will suffer significant harm in 2020 that will never be recovered, but the trajectory of free cash flow starting in 2021 will return to the trend level of the exhibit above. Under this scenario, your intrinsic value estimate would decline by the un-discounted $10 million of lost free cash flow for 2020 and the value of the enterprise would decline by about 6 percent to $156.3 million.

Adding a little complexity, let’s say that you believe that the $10 million of lost free cash flow in 2020 will be partially offset by a $5 million of additional free cash flow in 2021 due to pent up demand, followed by a return to the prior trend level. In this case, intrinsic value drops by only 3.2 percent to $160.9 million as shown in the exhibit below:

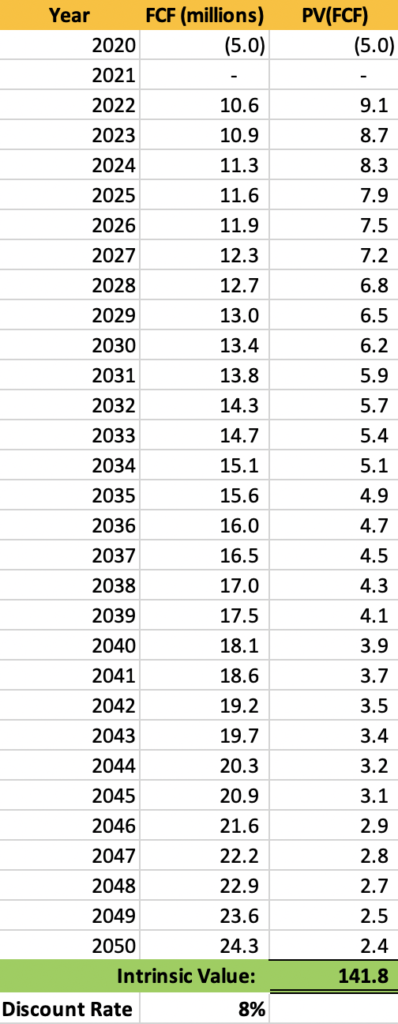

But let’s say that the scenario is going to get much worse before it gets better. You expect negative FCF of $5 million in 2020, no free cash flow in 2021, and then a return to the prior trend level of free cash flow thereafter. Under this scenario, intrinsic value falls 14.7 percent to $141.8 million as seen in the exhibit below:

There are an endless number of permutations that are possible and the examples above are simplistic, but should serve to make two very important points:

- Focus on business impact first, valuation later. The real question facing investors is accurately assessing the near and long term impact of a pandemic-related business slowdown and correctly ascertaining whether the business has enough of a margin of safety to weather the short term and survive to see the long term.

- Focus on long term impact, not short term pain. The vast majority of the intrinsic value of a business is typically attributed to expected cash flows in the intermediate and distant future. While the short run impact can be painful, so long as a business can both survive in the short run and not suffer any long term impairment to its cash generating capabilities, the decline in intrinsic value is not likely to be calamitous.

Markets are emotional and capricious because human beings are emotional and capricious. Intelligent investors will have prepared for temporary disruptions in business activity by avoiding excessively leveraged businesses lacking a margin of safety and will attempt to make intelligent assessments of the long term prospects for the business. Then, if markets insist on marking down a business by fifty percent when a rational assessment indicates only a minor reduction in value, the intelligent investor can be poised to act by accumulating more shares with cash available as the fruit of prior sound long term decisions.

Berkshire’s Repurchase Prospects

It seems like much more than one week has passed since Berkshire Hathaway investors were immersed in reviewing the company’s 2019 annual report and Warren Buffett’s annual letter to shareholders. The content and context of the letter seemed to reinforce the idea that Berkshire is likely to repurchase shares in the future.

Much information regarding Berkshire’s past repurchase history can be found in this article published on The Rational Walk last week and readers are encouraged to review that information before considering this brief update.

One of the problems with static thinking when it comes to prospects for repurchases is that it does not reflect how Warren Buffett thinks about his opportunities to deploy Berkshire’s cash. Buffett does not fixate on book value at the end of 2019 when it comes to deciding whether to repurchase shares today and has de-emphasized book value as a relevant metric in general. Furthermore, it is likely that his thoughts regarding capital allocation have changed over the past week due to the decline in stock prices in general and Berkshire’s stock price in particular.

Although book value has been de-emphasized, it is still a relatively useful yardstick since it governed Berkshire’s repurchase policy until mid-2018. Since the policy was changed, Berkshire’s repurchases have fallen within a range of 1.25-1.43x the last reported book value, as discussed in last week’s article.

As of Friday, February 28, Berkshire’s Class A shares closed at $309,096 which is down 10 percent for the week, compared to the 11.5 percent decline for the S&P 500 index. Berkshire trades at a price-to-book ratio of just 1.18x based on December 31, 2019 book value which is far below the level at which recent repurchases took place.

This might seem to make repurchases a no-brainer, but of course Berkshire’s book value as of today is almost certainly lower than it was at December 31, 2019 due to declines in its large portfolio of common stocks. Based on my calculations, the stock positions reported on Form 13-F have declined by 12.1 percent year-to-date, assuming that the positions remain unchanged so far this year. This amounts to a decline of 12.1 percent, or $29.3 billion! Even accounting for a reduction in deferred tax liability, this hit to book value is probably in the neighborhood of $23 billion.

As an offset to this decline, Berkshire has almost certainly posted very significant net operating income year-to-date. If the run-rate over the past couple of years held constant for January and February, Berkshire likely posted about $4 billion of net operating income.

If the assumptions above are in the ballpark, Berkshire’s book value probably declined by around $19 billion year-to-date which would reduce book value per share from $261,417 at December 31, 2019 to around $250,000 per share today. That would put the current price-to-book ratio at around 1.24x which is still on the very low end of where Berkshire has repurchased in the past.

With $125 billion of cash on the balance sheet, Warren Buffett could have deployed a billion dollars or more to repurchase stock during the market decline of the past week, and that is only considering the volume on the public markets. He also opened up the possibility of private repurchases in his annual letter in amounts of $20 million or more. According to Yahoo! Finance, Class A volume was 2,900 shares and Class B volume was 49,481,700 from February 24 to 28 which is meaningfully higher than normal. I have not attempted to calculate the dollar volume with precision but it seems to have been in excess of $11 billion for the week.

Of course, whether any shares were repurchased also depends on the alternatives that became available during the week. Many of Berkshire’s top holdings, especially in banks and airlines, suffered declines last week far greater than Berkshire’s decline. Additionally, it is possible that other opportunities have come up since Buffett’s willingness to make big bets during a crisis is now well known. His phone might have been ringing quite a bit last week.

Further discussion regarding repurchases can only delve into speculation at this point. We will know how many shares, if any, were repurchased during last week’s tumultuous markets when Berkshire reports first quarter results in early May.

Concluding Thoughts

Markets can do anything in the short run and investors should never forget this fact. Long periods of quiet in financial markets lull investors into a false sense of security and long periods of steady gains feed complacency. When markets tumble, coping with meltdowns in ways other than panic selling becomes imperative.

Timeframe arbitrage is perhaps the only enduring advantage that most individual investors have left. It isn’t impossible to have differentiated insights ignored by professionals, and many individuals outperform on that basis. But for the rest of us, knowing when to focus on the long term when everyone else is focusing on next quarter becomes a huge advantage. At the same time, we should not deceive ourselves into thinking that we have not personally taken some sort of hit when an unexpected event like Coronavirus disrupts business activity. Almost all of us are somewhat poorer as a result.

Most professional investors managing capital for others lack the luxury of thinking about the next three years because they are obsessed with what they will report to investors over the next three months. That’s just the inherent bias of most people moving large amounts of money in the markets and isn’t likely to change. As an individual investor accountable to no one but myself, I don’t intend to needlessly adopt this dysfunctional mentality.

Disclosure: Individuals associated with The Rational Walk LLC own shares of Berkshire Hathaway.

- The daily Treasury yield curve database is a useful way to track government bond yields. [↩]

- There are many sources of information on Coronavirus in the mainstream media, and many others, including Bill Gates, have sounded alarms regarding the situation. I have no expertise in the science behind the virus and no special insights beyond what has been widely published. Therefore, this article is mostly about how I would think about the impact of a pandemic on the value of financial assets, an area where I (hopefully) have some insights to share. [↩]